Lexical Analysis

-

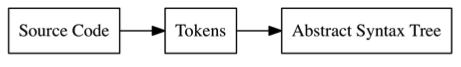

we represent our source code in other forms that are easier to work with. We are going to change the representation of our source code 2 times before we evaluate it:

-

Transformations from source code to tokens → lexical analysis or lexing for short. Its’ done by a lexer(also called as a tokenizer or scanner).

-

Tokens itself are small, easily categorisable data structures that are fed to the parser, which does the second transformation and turns the tokens into an “Abstract Syntax Tree”.

-

Eg:

- for the input code :

let x = 5 + 5; - we get out of the lexer:

[ LET, IDENTIFIER("x"), EQUAL_SIGN, INTEGER(5), PLUS_SIGN, INTEGER(5), SEMICOLON ] - for the input code :

-

Whitespace characters don’t show up as tokens.In our case that’s okay, since whitespace length has no significance in Vanara language. Whitespace merely acts as a separator for other tokens.

-

A production-ready lexer might also attach the line number, column number and filename to a token. Why ? Eg: to later output more useful error messages in the parsing stage.

Defining our tokens:

let five = 5;

let ten = 10;

let add = fn(x,y) {

x + y;

};

let result = add(fice,ten);- numbers are just integers and we are going to treat them as such and give them a seperate type.

- Our lexer or parser we dont care if the numbers is 5 or 10, we want to just know if it is a number or not.

- same goes for variable names → call them as “identifiers” and treat them the same. ie. the ones that look like identifiers, but aren’t really identifiers, since they are part of the language, are called as “keywords”. Won’t group them together since it should make a difference in the parsing stage whether we encounter a let or fn.

- For special characters we would treat each of them seperately.

- Token data structure:

- need a type attribute so we can distinguish between integers and right bracket.

- Also needs a field that holds the literal value of the token so we can reuse it later and the information whether a number token is a 5 or a 10 doesnt get lost.

- TokenType is to be a string, allows us to encode many different values as TokenTypes , which in turn allows us to distinguished between different types of tokens.

- Using string also has the advantage of being easy to debug without a lot of boilerplate and helper functions: we can just print a string.

- We have a limited number of different token types in the Vanara language, so that we can define the possible TokenTypes as constants.

- Two special tokens that we are considering:

- ILLEGAL → signifies a token/character that we don’t know

- EOF → stands for “end of file”, which tells our parser later on that it can stop.

Lexer:

- It will take source code as input and output the tokens that represent the source code. It will go through its input and output the next token it recognizes.

- It doesn’t need to buffer of save tokens, since there will be only one method

NextToken(), which will output the next token. - Initialize the lexer with the our source code and then repeatedly call

NextToken()on it to go through the source code, token by token, character by character. We also make life simpler here by using string as the type for our source code. - Our lexer will have the following structure:

type Lexer struct {

input string

position int // current position in input (points to current char)

readPosition int // current reading position in input (after current char)

ch byte // current char under examination

}- the reason for these 2 “pointers” pointing into our input string is the fact that we will need to be able to “peek” further into the input and look after the current character to see what comes up next.

- readPosition always points to the ‘next’ characters in the input. position points to the character in the input that corresponds to the ch byte.

readChar():- Purpose is to give us the next character and advance our position in the input string.

- First thing to check whether we have reached the end of input.

- If yes, then set l.ch to 0 i.e the ASCII for NULL. and signfies either “we havent read anything yet” or “end of file” for us.

- If we havent reached the end of input yet, it will set l.ch to the next character by accessing

l.input[l.readPositon]. - After that

l.positionis updated to the just usedl.readPositionandl.readPositionis incremented by one. That way, l.readPosition always points to the next position where we are going to read from next andl.positionalways points to the position where we last read. - Currently to support Unicode and UTF-8 , we would need to change l.ch from a byte to rune and change the way we read the next characters, since they could be multiple bytes wide now. Using

l.input[l.readPosition]wouldn’t work anymore. - Extending our lexer:

- Our lexer needs to do is recognize whether the current character is a letter and if so, it needs to read the rest of the identifier/keyword until it encounters a non-letter-character.

- adding a default branch to our switch stmt , so we can check for identifiers whenever the l.ch is not one of the recognized characters. Also added the generation of token.ILLEGAL tokens. If we end up there, we truly don’t know how to handle the current character and declare it as token.ILLEGAL.

isLetter()checks whether the given argument is a letter. That sounds easy enough, butisLetter()is that changing this function has a larger impact on the language our interpreter will be able to parse than one would expect from such a small function.

LoookupIdentchecks the keywords table to see whether the given identifier is in fact a keyword. If it is, it will return the keyword’s TokenType constant. If it is not, we will just get back token.IDENT, which is in fact the TokenType for all user-defined identifiers.- in the return tok statement, is necessary because when calling

readIdentifier()we callreadChar()repeatedly and advance our readPosition and position fields past the last character of the current identifier.

- in the return tok statement, is necessary because when calling

skipWhiteSpace()is a little helper function which is found in a lot of parsers. Sometimes calledeatWhiteSpace()etc. Which characters these functions actually skips depends on the language being lexed. Some language implementationms do create tokens for newline characters and then throw parsing errors if they are not at the correct place in the stream of tokens.readNumber()method is exactly the same asreadIndentifier()except for its usage ofisDigit()instead ofisLetter. We can probably generalize this by passing in the characters-identifiying functions as arguments.- Notice due to the educational aim of this book , we only read in integers, not floats or numbers or octal notation, and just ignore them (for now!)

Extending Token Set and Lexer:

- The new tokens that we will need to add, build and output can be classified as one of these 3 :

- one-character token (eg: -)

- two-character token (eg:

==) - keyword token (eg:

return)